Introduction by Julia Katherine, Director for Education

In Surrey, we believe every child deserves the chance to reach their full potential. We are committed to ensuring that all children have access to high-quality, inclusive education within their local communities.

Guided by our ‘Time for Kids’ principles, we are dedicated to creating learning environments that are responsive to the diverse needs of every child, enabling them to develop a sense of belonging within their school community.

The Ordinarily Available Provision (OAP) Guidance is a practical tool designed to help schools deliver the best quality education tailored to the individual needs of each child. This revised document serves as an accessible, everyday guide, reflecting real-life school situations and experiences.

This resource has been shaped by the invaluable insights and dedication of school leaders, Special Educational Needs Coordinators (SENCos), parents, carers, and children. We are deeply grateful for their contributions to the co-design process. Together, we can promote meaningful independence in school environments where every child feels valued, supported, and empowered to succeed in their unique way.

By adopting a consistent, whole-school approach to Ordinarily Available Provision, we aim to strengthen inclusive practice and ensure equitable opportunities for all children to thrive. By fostering positive relationships between schools, families, and other professionals, we hope to meet children's needs at the earliest opportunity, ensuring no learner is left behind .

Supporting statement from School SENCos

“From co-producing the OAP, I’ve seen first-hand how bringing together different professionals helps make the document genuinely useful across the whole school. It’s not just about supporting pupils with Special Educational Needs (SEN) — it’s about building the confidence and skills of staff too. In our school, the OAP helped us to support understand of their journey clearly and recognise when the right time was to apply for an Education Health and Care (EHC) plan. That process felt less overwhelming because we had the OAP as a shared reference point. It’s a tool that really makes a difference when it’s shaped by everyone."

Primary and Nursery School Special Education Needs Coordinator (SENCo)

A huge thank you to..

The children at Broadwater School, Danetree Primary School, Darley Dene Primary School, Glyn School, Oxted School, Sythwood Primary School, and Westfield Primary School — thank you for your invaluable contribution and perspective on school life. Your comments and lived experiences have provided a valuable insight into what everyday life in school is like for you, and we hope you see yourselves and hear your voices reflected throughout this document.

We also extend gratitude to the school staff, subject matter experts, partners, and stakeholders who have contributed to this review — whether as members of the review group, participants in the working groups, reviewers of documentation, or as host schools providing us with the opportunity to hear the ‘child’s voice.’ Your engagement, expertise, insights, and viewpoints have enriched and shaped this project beyond expectation.

This resource is the result of a collaborative effort involving many, and we hope the relationships built during this review period will continue to support our shared goal of improving outcomes for children.

Overview

Ordinarily Available Provision – Section A

This section includes a clear definition, and key principles of OAP, as collaboratively designed, in partnership, with Surrey SENCo school colleagues. These underpin the way OAP should be applied in schools.

Importance of Relationships

This section describes the impact of positive relationships that nurture a sense of belonging for the whole school community. It is relevant for parents, school leaders, teachers, SENCos, and all other schools staff.

Support around the Child

This section is especially relevant for parents, teachers, and SENCos where concerns persist despite High Quality Teaching.

Reasonable adjustments

This section includes a description of reasonable adjustments, with a focus on inclusive practice and removing barriers to learning, what the law says, and seeks to clarify what is and is not ‘reasonable’.

High Quality Teaching

'High quality teaching', as described in the SEND Code of Practice, is teaching that is differentiated and personalised to meet the needs of children where progress:

- is significantly slower than that of their peers starting from the same baseline

- fails to match or better the child’s previous rate of progress

- fails to close the attainment gap between the child and their peers

- widens the attainment gap

High quality teaching considers the needs of children in schools to inform planning and delivery to make learning accessible. This may involve teaching staff using the examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustments and specific interventions, detailed in section three, to support children to learn, access and engage with the curriculum.

This section can be used to facilitate conversations between children, parents, and schools, and can be understood as the requirement for a school to take positive steps to ensure that all children can fully participate in the education provided by the school, and that they can enjoy the benefits, facilities, and services that the school provides.

Ordinarily Available Provision – Section B

Contains practical examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustments and specific interventions to support children in schools. The strategies in this section should be used alongside High Quality Teaching, based on the needs of individual children. Schools are not expected to deliver all of the strategies, rather they should make adjustments and apply appropriate support based on the skills and resources available to the school.

It is of relevance to teachers, SENCos and school leaders when determining the school's SEND offer in relation to their learners' additional needs. It will also support conversations between schools and parents to ensure the right support can be prioritised at the right time.

Shared practice

In this section you will find examples of practice shared by schools, used to support children in school.

Ordinarily Available Provision – Section A

Definition of Ordinarily Available Provision (OAP)

OAP is part of a school’s approach to inclusive education based on individual needs. It removes barriers to progress and supports the development of every child. It forms part of everyday provision that schools are expected to deliver, within their resources, and is available to all children as part of high-quality teaching and learning practice.

Key principles of OAP

- Empowers children and young people to be independent and develop their decision making in preparation for adulthood.

- Takes a personalised approach that acknowledges success looks different for everyone.

- Holds the views and aspirations of children, young people and their families central to planning, and ensures they are included in decision making.

- Ensures assessment and intervention focus on identified needs and not a diagnosis. This refers to a need led approach that centres on inclusion and adaptations.

- Is a whole school approach, where inclusion is fully integrated, not something extra.

- Places a strong focus on inclusive practice where schools endeavour to remove barriers to learning, adapt to support progress and social inclusion, create environments that offer a strong sense of belonging for all learners.

Importance of relationships

“We thought we were good at relationships and that we held them in high regard. (After attending the Relational Practice Whole School Leadership Programme) We realised that we had more to do and that our actions were not intentional enough in ensuring relationships were at the heart of everything we do.”

(Head Teacher)

Relationships are essential for creating a successful and supportive school community where everyone belongs, and learning can take place. Relational practice is a way of being, a fundamental ethos which provides an environment where healthy relationships are fostered, where there is both, high support, and high challenge. It underpins and aligns with the Surrey Healthy Schools approach.

A relational approach is evidenced through the daily interactions and culture of the school, promoting trust, empathy, and mutual respect among children and young people, parents, carers and the wider school team.

When relationships are at the heart of everything we do, the community feels connected, there is increased engagement, and everyone thrives both socially and academically.

Relational practice is about proactive relationship building and maintenance, reducing conflict and enabling resolution and repair. Relational communities seek to understand behaviour, show curiosity and acknowledge all behaviour as a form of communication. Having well established positive relationships with children and families leads to a secure foundation on which to build when additional support is needed. When additional support is needed it is provided in a restorative way where everyone is involved in what happens next and in deciding how to move forward.

Benefits of relational practice

For children

- Higher engagement: Feeling valued boosts motivation.

- Positive behaviour: Reduces behaviour that challenges.

- Stronger social skills: Develops communication, empathy, and teamwork. Includes a positive impact on attendance.

- Supports mental health and emotional well-being

For Teachers and Teaching staff

- Improved classroom environment: Fewer disruptions, more cooperation

- Job satisfaction: Meaningful connections lead to a more positive experience

- Better collaboration: Stronger relationships between teachers, children and parents

For the Whole School

- Increased sense of belonging: Fosters inclusivity and respect

- Higher academic performance: Studies link relationships to better learning outcomes

- Reduces conflict, bullying and discipline problems

- Creates a safe learning space where children feel respected

- Prepares children for future career, relationships, and lifelong success

- Aligns with school goals: Equity, inclusion, and positive school culture

Relational practice in OAP

Build strong relationships:

- Prioritise getting to know children and colleagues

- Show genuine interest in their lives and experiences

Create safe spaces:

- Ensure that children feel respected and understood

- Foster an environment where children feel safe to express themselves and take risks in learning

Listen with purpose:

- Actively listen to children’s concerns and needs

- Validate children’s feelings and experiences. This will help build trust

Model positive behaviour:

- Demonstrate the behaviour you would like to see from children

- Show kindness, open-mindedness, empathy, in your interactions

Collaborate with families and colleagues:

- Work together to provide consistent support for children

- Engage parents and external agencies to create a unified approach

Understand and respond to behaviour:

- Understand behaviour is a form of communication

- Address underlying needs rather than just managing symptoms

Provide ongoing support and training:

- Invest in continuous professional development for all staff, including support staff and staff not based in the classroom

- Offer regular meetings, supervision, and coaching to maintain skills

Before – What children said before restorative conversations where part of everyday practice

“I don’t think they like me because they always give me strikes.”

“I always get sent out, but I can’t help it.”

“You get a strike if you do something naughty, but only if you get caught!”

“I don’t always tell the truth because I don’t want to get into trouble”

“I don’t want to get anyone in to trouble or be called a tell-tale (when teachers ask children who weren’t involved in an incident what happened)”

“I don’t care, so red cards don’t work.”

After – What children said about restorative conversations once embedded in everyday school practice

“I trust my teacher more now and feel less worried about speaking to her when something happens because I know it will be dealt with in a fair way.”

“My friends were all arguing, we managed to sort it ourselves by listening to each other. We didn’t need to tell anyone, and we are all friends again now.”

What teaching staff said about restorative conversations

“They take away the anxiety of being shamed. The child is not ‘told off’ but there is still a consequence, a logical one.’

“Restorative conversations have been illuminating and have helped me view incidents in a different way. I thought I knew what was happening when I observed a situation, but I realised when I listened to the children’s perspective that I had misunderstood.”

“They help you build better relationships with the children. They build trust and support the children to take responsibility for their behaviour.”

“They (children) know they aren’t going to get in trouble, so they are more likely to be honest about what happened.”

“Because they have been involved, the children accept the consequences and take ownership, they understand why it has been given.”

“Children know the incident will be dealt with in a fair way. The structure (of the restorative conversation…) is predictable and everyone gets their say.”

Support around the child

All children in Surrey schools’ benefit from high-quality teaching and universal support, enabling the majority to thrive and make strong progress.

At times—and not solely in relation to educational needs—some children may require additional support. In such instances, schools can refer to the Ordinarily Available Provision (OAP) document to identify reasonable adjustments, minor adaptations, and supportive strategies that can be scaffolded around the child to help them continue to make the progress we know they are capable of.

If a child is not making progress, despite the above, schools can look at providing SEND support for the child, in the form of appropriate interventions.

All the above should be considered alongside conversations with parent/carer to understand if anything at home is impacting on school life.

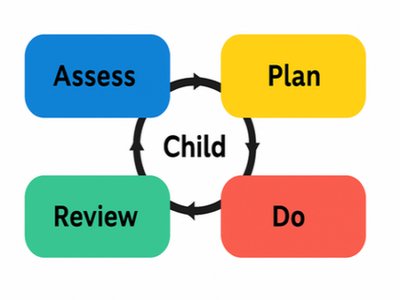

Assess, Plan, Do and Review

The support and actions put in place by the school to meet a child’s needs will usually be re-visited, reviewed, and refined. This allows for increased focus and informed provision to be put in place. These actions aim to ensure children can make good progress and better access the school curriculum. This is often referred to as a graduated response.

For most children, high quality teaching strategies remove potential barriers to learning and enable progress. Where there is evidence of ongoing difficulties that prevent progress, indicating the need for additional support and/or provision, the school should apply the four-part model outlined in the SEND Code of Practice: assess, plan, do, review.

Assess

- What is happening for the child?

- How does the child describe their needs/difficulties?

- What are the parents seeing at home?

- Is there a pattern i.e. a particular lesson/environment

Plan

- What additional High Quality Teaching strategies could support the child?

- What additional provision and resources are needed to meet needs?

- Best time for the support to take place?

- Who is best placed to act as point of contact, deliver and review additional support?

- Best way to measure impact?

Do

- Deliver agreed support strategies and note differences made.

- Refine strategies to maximise the effect they have.

- Ensure that additional provision is delivered as it is meant to be

- Observe and gather feedback.

Review

- What adjustments are needed based on observations and feedback?

- What worked well, what didn’t work well?

- Did the child make sustainable progress?

- Identify next steps. Is further support needed?

- Is further training needed for the staff team?

Reasonable adjustments

All children should be helped to fulfil their potential. Reasonable adjustments can help to create equity by minimising the disadvantages that children might face compared with their peers.

Most reasonable adjustments are amendments made to policy and practice, that are straightforward to implement, where teaching staff recognise barriers to learning and see the benefits the adjustments have for children. Whilst there is no requirement to change policies for all pupils, adaptive learning environments provide the best opportunities for all children to succeed.

Whilst it is not possible to say what is and is not reasonable, because situations and circumstances are different, schools are encouraged to consider the following when thinking about the reasonable adjustments they can make:

- What is already in place?

- Cost and resources available to the school

- Potential impact/outcomes

- Is it practical?

- Health and safety requirements

- Impact on school standards (incl. academic, musical, sporting)

- Interests of other pupils and prospective pupils

You can read more about the Equality Act Guide for schools in the National Children's Bureau guidance Disabled Children and the Equality Act 2010: What teachers need to know and what schools need to do.

Examples of reasonable adjustments

What are reasonable adjustments and how do they help disabled pupils at school? gives more information on reasonable adjustments, including examples.

When putting reasonable adjustments in place, it is important, in all instances that a member of the school staff team is allocated as a point of contact between home and school, to agree what can be put in place, a timeframe, and dates for review. The same member of school staff should check in with the child daily, to ensure the adjustment is appropriate, and to understand if further adjustments are needed. This may include increasing, extending, or ending the adjustment.

- child with a broken foot who requires adjustments to the school uniform (footwear) to accommodate the injury for a fixed period, determined by need.

- a child who has experienced a bereavement, requires temporary adjustments to their timetable to support them throughout the grieving process.

- a child who experiences panic attacks is permitted to remove their school tie as and when required

- a child who has recently been observed struggling to manage their emotions in class has a conversation with a trusted adult, they agree that a movement break card may help. This permits the child to leave the class when needed.

- a child who becomes dysregulated when unclear about what happens next in school is permitted to wear a smart watch with their timetable

- a child with a visual impairment is able to leave the classroom early to ensure they can easily move through the corridors before everyone starts to move around

- a child with a visual impairment sits at the back of the class to accommodate their field of vision.

- an inclusive and considered Whole School Food Policy is implemented to enable a child with diabetes to consume a high-calorie snack at breaktime.

- school uniform is adapted for a child who has an allergy to synthetic material or severe eczema.

- communication systems like traffic light cards are put in place for a pupil who needs extra time to complete a task.

- a child with specific literacy difficulties i.e. dyslexia, has a printout of Interactive Whiteboard presentations to make reading and tracking text easier.

- a short-term reduced timetable, which is reviewed regularly, is agreed for a child with Autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or other neuro-divergence (ND) who finds classroom environments overwhelming, to build their confidence back up to full time attendance.

Working with children and families to make adjustments can increase attendance, improve behaviour, and contribute to building positive relationships. Schools are encouraged to discuss reasonable adjustments with parents and Children, who may be able to provide insight that offers innovative solutions.

The SEND code of practice: 0 to 25 years states:

‘In practical situations in everyday settings, the best early years settings, schools and colleges do what is necessary to enable children and young people to develop, learn, participate and achieve the best possible outcomes irrespective of whether that is through reasonable adjustments for a disabled child or young person or special educational provision for a child or young person with SEN.’

Schools should assess each child’s current skills and levels of attainment on entry, building on any information provided by previous settings and key stages where appropriate. At the same time, schools should consider evidence that a pupil may have a disability under the Equality Act 2010 and, if so, what reasonable adjustments may need to be made for them.

They must make reasonable adjustments, including the provision of auxiliary aids and services, to ensure that disabled children and young people are not at a substantial disadvantage compared with their peers. This duty is anticipatory – it requires thought to be given in advance to what disabled children and young people might require and what adjustments might need to be made to prevent that disadvantage.

Further detail on disability discrimination duties in schools can be found on page 3 of the Disabled Children and the Equality Act 2010: What teachers need to know and what schools need to do.

High quality teaching

Provision and coproduction with children, parent and carers

Expectation 1

There is an embedded commitment to work in partnership with parents, carers and children to maintain a person-centred approach.

Children told us

‘At my school I have a key worker who comes and gets me from my tutor group to check on me and make sure everything is ok. My mum and dad can speak to the key worker when they need to.’ Key Stage 4 child

‘Some children have difficulties, like my brother. He struggles quite a bit, so I go to a special group, and we do cooking or crafts and stuff. It helps me and I have different friends there.’ Key stage 2 child

‘We have a Student Council, but it’s for everyone, not just SEN people. Some teachers ask what we think about stuff. They asked us about Sparx Maths and what would make it better and then they changed it.’ Key stage 4 child

Characteristics of good practice

- Parents, carers and children have a named contact who they can speak to. This may be the child’s head of year, SENCo, or another suitable person.

- Families can access a range of formal and informal ways of sharing information about children. This may include, but is not limited to, child and parent surveys, coffee mornings, use of a home school diary, information placed in book bag, text or email. Parents and carers are actively encouraged and supported to contribute.

- Parents and carers are signposted appropriately to Surrey’s Local Offer website via the school.

- Parents can access the OAP for Schools guidance on the school website.

- Parents and carers are actively encouraged and supported to contribute to support plans.

- Every school/setting has a SEND information report which is coproduced with parents/carers and updated annually.

- Formal and informal events take place to seek views in relation to SEND from both family carers and children e.g., school council.

Expectation 2

Effective partnerships with children and their parents are evident through participation in the assessment and review processes. The voice of the child is central to the support and interventions put in place.

Children told us

‘Sometimes I feel scared and don’t want to do learning at school. Drawing makes me feel better, then I can join in with my friends.’ Key stage 1 child

‘If we are having a difficult day we can ask to go and see the Reading Dog. That helps me to relax for a bit.’ Key stage 2 child

‘I used to sit in the front row because I needed extra help. I don’t need so much help now, so I can choose where to sit in any of the other rows.’ Key stage 1 child

Characteristics of good practice

- Parents and carers are aware of their child’s learning needs, the support, and any individually tailored interventions in place.

- Children are aware of their own learning needs, the support in place, as well as any additional support that may be available to them. Children are informed when they are accessing interventions, and when the intervention has come to an end, so that there is an opportunity to reflect on the learning and to plan next steps.

- Targets are coproduced and reviewed with parents, carers and the children themselves.

- Children are supported to understand the difficulties they are experiencing and the

- strategies they can use to overcome these difficulties.

- Children understand and can contribute to the targets they are working to achieve.

- Child’s strengths and aspirations are key to the support put in place.

- The parent and children’s expertise are actively sought to inform strategies of support

Pastoral Care

Expectation

Children feel safe, valued and cared for. school staff are supportive and responsive to the needs of children and manage concerns appropriately.

Children told us

‘When the teacher knows me, I feel better because they know what I’m like and what I need.' Key stage 3 child

‘Having a teacher or someone, I can go to when I need them, helps me feel safe and calm.’ Key stage 3 child

‘If I am worried, I can use my ‘Worry Bubble’ then the teacher will come and find me to talk about it.’ Key stage 2 child

‘I have dyslexia, and we all get given coloured overlays. They don’t help me, so the teacher just gives me a bit more time to read things and doesn’t make me read out loud.’ Key stage 4 child

‘There is some bullying, and we talk in class and assembly about how to treat our friends. The Headteacher always takes it seriously so that’s who I tell.’ Key Stage 2 child

‘I have a movement card so that I can leave the class if I need to. Sometimes I pop out and come back, other times I go to the SEND room and chat with the teacher. That stops me getting in big trouble.’ Key stage 4 child

‘In tutor we talk about relationships and stuff about looking after ourselves.’ Key stage 4 child

Characteristics of good practice

- Children feel they are listened to, heard, and treated with respect.

- There is a calm and purposeful learning environment where children belong, feel welcome, and that their contributions are valued

- Children can identify an agreed safe space that they can access and use when they need it.

- Relationships are at the heart of the school’s culture. Relational and Restorative Practice is evidenced through the school values, behaviour and teaching and learning policies. Everyone in the school community demonstrates positive regard for each other.

- The school/setting fosters a culture of self-help, cooperation, and collaboration. A range of strategies are used to promote peer support.

- Personal, Social, Health and Economic (PSHE) education is proactively planned to help develop a sense of belonging, self-esteem, health and wellbeing along with skills to develop social and emotional literacy, assertiveness, decision making and resilience.

- Children have opportunities to understand their own needs and reflect on the needs of others

- Peer awareness and sensitivity towards difference e.g., SEND and protected characteristics, are raised at a whole school level. Work is then carried out with classes and groups regarding specific needs or conditions as appropriate.

- Difference is accepted with all children included and represented across all aspects of school life.

- The language used in school/setting is positive and encouraging

- Unconscious bias training is available for all staff

- See relevant policies as set out in Theme 1 of the Surrey Healthy Schools approach.

- Children know a trusted adult/teacher/person they can talk to when they have a concern. They know how, where and when they can reach them.

- The setting promotes positive attitudes, beliefs and practices towards individuals and groups

- The staff in the setting model positive attitudes, beliefs, and practices.

- The views of children are sought regularly to identify and implement improvements.

- Children are ready to learn before teaching begins and teachers are equipped with a collection of strategies for this

- Staff and teachers listen so that children, parents and carers feel that they have been heard, and their concerns have been acknowledged and addressed accordingly

Physical and sensory environment

Please read in conjunction with the section on reasonable adjustments.

Expectation 1

The physical environment is adapted to meet the needs of children and young people.

Children told us

‘I get lesson notes printed for me, so that I don’t have to keep stopping what I’m doing to look up at the board. I get lost when I do that.’ Key stage 4 child

‘It can be difficult to know what to do, who to talk to, at break/lunch so it’s nice to know I can go to the library/LRC and be quiet there.’ Key stage 3 child

‘It helps me stay calm if I can leave lessons 5 minutes early to get to my next class.’ Key stage 3 child

‘It helps me when the tables are set up so I can walk around them, without bumping into them’ Key stage 4 child.

Characteristics of good practice

- All settings have an accessibility plan which is published on their website.

- Reasonable adjustments are made according to individual needs.

- The furniture is the appropriate size and height for the child.

- Extra-curricular activities and educational visits are planned to fully include children with SEND (in line with the Equality Act 2010), including those with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) and physical disabilities

- Children’s views are routinely sought and are used to inform in planning for physical or sensory adaptations that they may require.

Expectation 2

Practitioners are aware of and adjust for children’s sensory needs which may include physical impairment e.g., hearing/ vision and sensory differences e.g., touch, smell, noise.

Children told us about

‘It really helps me if I can have a space to work quietly and on my own.’ Key stage 4 child

‘The science rooms are like a greenhouse. Some teachers turn the lights off which helps and let us remove our blazers.’ Key Stage 4 child

Characteristics of good practice

The following adjustments have been considered and applied where appropriate:

- Seating arrangements

- Movement breaks

- Equipment

- Environmental modifications e.g., reduced sensory overload, lighting, displays.

- Presentation of materials e.g., text size, colour, background.

- Noise management e.g., noise cancelling headphones, a quiet area to work.

- Access to alternative spaces e.g., due to smell or noise.

- Flexible uniform policy

Teaching and learning strategies

Expectation 1

Practitioners understand the nature of children’s needs, the impacts their needs have, and how to respond to them.

Children told us

‘We stay in our tutor groups for all lessons. After progress checks we go in sets. I think sets are good because we’re all at the same level.’ Key stage 3 child

Characteristics of good practice

- Practitioners carry out assessments through teaching, screening tools and standardised assessments so that they understand the child’s strengths and if there are gaps in learning.

- Practitioners use this information to coproduce targets and interventions with the child and family carers.

Expectation 2

Practitioners differentiate to provide suitable learning challenges and cater for different learning needs and styles.

Individualised and small group planning and programmes in more than one curriculum area.

Use of approaches to promote independence, scaffold, and support children.

Children told us

‘We have printed copies of our timetable so we know where to go next. Some people have pictures to show what lesson they’ve got, food for lunch time etc, they have words too.’ Key stage 3 child

‘Teacher tells us what we are doing, gives an example on the flip chart and this stays up whilst we are doing it. Teacher reminds us to look at the flip chart before we ask for help.’ Key stage 2 child

‘Some teachers leave examples on the whiteboard as reminders - I forget things if I can’t see them.’ Key stage 3 child

Characteristics of good practice

Strategies that support differentiation include:

- visual timetables, clear concise instructions with written or visual prompts (e.g., now, and next cards), particularly during transitions.

- additional time to process information before being asked to respond.

- breaking down tasks into small manageable steps which are explicitly taught.

- varied pace, content, and order of activities to support access and engagement

- modelling is used to aid understanding.

- repeated learning to promote fluency and planning for generalisation of newly learnt skills.

- key vocabulary is displayed with visuals.

- alternatives to written recording are used routinely.

- study skills are explicitly taught.

- Children have access to homework clubs, or additional support with homework

- homework is differentiated appropriately for the child.

- Know and incorporate children’s interests.

Expectation 3

Every teacher is a teacher of SEND: Teachers adapt their approaches and can support a range of needs through an adapted approach.

Children told us

We have this teacher who uses sport to teach Maths. He knows we love sport so and it helps. It’s brilliant!’ Key stage 4 child

‘Teacher helps us but we have to try first before asking for help.’ Key stage 1 child

‘We got to learn some British Sign Language. We got to show it at an open evening for new people. It was so good. I’d like to do more.’ Key stage 3 child

Characteristics of good practice

- Strategies are used to actively promote independent learning through overlearning and appropriately differentiated resources.

- Seating plans and groupings considering individual needs and routinely provide opportunities for access to role-models, mixed-ability groups.

- Provide planned opportunities for children to generalise newly learnt skills.

- Study skills are explicitly taught. Children and young people have access to homework clubs, or additional support with homework.

Expectation 4

Practitioners ensure that collaborative learning and peer support is a feature of lessons.

Children told us

‘One child in the class can choose a friend who goes with them early to lunch. It helps to avoid queueing and gets extra outside after lunch and stops them feeling anxious.’ Key stage 1 child

Characteristics of good practice

- Strategies are used to build and maintain positive relationships across the whole school community (e.g., restorative approaches).

- There are opportunities to develop peer awareness, sensitivity and support for different needs and disabilities both in and out of the classroom.

Equipment and resources

Expectation 1

Equipment and resources are allocated appropriately to ensure additional needs are met.

Children told us

‘We have a box of toys in the classroom to help us concentrate.’ Key stage 2 child

‘Emotional toolbox has headphones if it’s too loud.’ Key stage 2 child

‘I have a wobbly cushion to sit on during carpet time.’ Key Stage 1 child

‘I can use a Chromebook, iPad or writing slope.’ Key stage 4 child

Characteristics of good practice

- There should be access to a range of equipment and resources to support children with sensory differences, sensory impairment, and physical disabilities.

- Use the Occupational Therapy resource finder

- Concrete apparatus and adapted resources are available for those children who require it.

- All equipment and resources should be available to pupils to support independent learning.

Expectation 2

Increased use of Information Communication Technology (ICT) resources to remove barriers to learning.

Children told us

‘Everyone has a Chromebook. My parents couldn’t afford it, so we got help from the school through Pupil Premium plus. It’s the same with buying uniform.’ Key stage 4 child

‘We can use the c-pens if we want.’ Key stage 4 child

Characteristics of good practice

ICT is used to support alternatives to written recording and to promote independent learning.

Expectation 3

Every setting should have a Continuing Professional Development (CPD) plan for all staff including teaching assistants so that they can meet the needs of all children.

Children told us

‘I have anxiety, so I get a ‘uniform card’. My card means I can take my tie off if I need to. I only use it when I’m stressed out, but some teachers, who don’t know me, get funny about it so I can just show them my card and it’s fine.’ Key stage 3 child

Characteristics of good practice

- There is a planned programme of ongoing CPD in relation to SEND for the whole setting and individual teams and departments.

- Best practice is shared within the school and with other schools via SENCo networks.

Expectation 4

Staff collaborate and have effective links with other relevant outside agencies and specialists.

Characteristics of good practice

- Practitioners know when to refer for extra support or advice

- The setting is aware of and regularly communicates with any other professionals who are involved with each child.

- Advice received from other professionals is adapted where appropriate and used to inform teaching and learning.

Expectation 5

Every setting has an induction programme for new staff which includes a robust focus on additional and special educational needs.

Children told us

‘We can go to the SEND room, there is always someone in there you can speak to. It’s a bit awkward when they don’t know you though.’ Key stage 3 child

Characteristics of good practice

- Induction programme in place for all new staff which includes:

- Working with parents

- Gaining pupil views

- Assessment

- Teaching and learning strategies

- Adapting the environment

- Understanding of key school policies e.g., safeguarding, inclusion

Skills and interest

Expectation 1

A regular cycle of Assess, Plan, Do, Review is used to ensure that children are making progress.

Characteristics of good practice

- Child’s strengths and difficulties in learning and behaviour are observed and monitored in different settings and contexts for a short period of time to inform planning.

- Staff are aware of children’s starting points so that expected progress can be measured across each key stage.

- Assessment is used to inform planning and interventions.

- Consideration is given for individual child developmental trends. Case studies are used to demonstrate holistic progress

Expectation 2

Practitioners ensure that formative assessment and feedback is a feature of lessons and evident in marking and assessment policy.

Characteristics of good practice

- A wide range of assessment strategies and tools are used to ensure a thorough understanding of leaners.

- Children have regular opportunities to evaluate their own performance.

- Self-assessment is routinely used to set individual targets.

- The impact of interventions is critically evaluated. Alternative approaches are explored to establish whether they may result in better outcomes for the child.

- Recommendations for screening tools can be found in Inclusion and Surrey Inclusion and Additional Needs Schools Service Offer.

Expectation 3

Expertise is in place to manage reasonable examination arrangements (access arrangements) for tests and national tests and public examinations.

Characteristics of good practice

- Schools make adaptions to assessment arrangements as part of everyday practice. This is used to establish the leaners normal way of working

- Adapted resources are used in class and assessments.

- Please refer to the relevant exam board guidelines. Arrangements may include: rest breaks, use of a reader, scribe, or laptop, extra time

Transition and change

Expectation

There is an effective process in place to support and plan for children joining and leaving their settings.

Primary school staff work in partnership with previous settings, including Early Years provision, to ensure the needs of the child are understood and planned for. Enhanced arrangements are made for pupils with additional and special needs.

Secondary school staff plan transition days for school children joining the school, includes in-year transfers where possible.

Schools and Early Years settings should work together to ensure the needs of the child are understood and planned for, and enhanced arrangements are made for pupils with additional and special needs.

Relationships with other settings are nurtured, in best interests of all children. This includes working together to discuss strategies and options to support the child throughout the transition period and beyond.

Children are supported to understand and manage transitions and predictable changes in their lives.

Staff are aware of those who will need additional support for all or most transitions and plan for this.

Staff understand how change may affect children and how to support them.

There are plans in place that enable staff to support children when unexpected change occurs.

This includes children who:

- Have insecure attachment, including but not limited to Children Looked After (CLA), Children in Need (CIN), Children on Protection plans (CP), children of serving forces families, and children who have social communication difficulty including English as an Additional Language (EAL)

- Suffered trauma, loss, or bereavement

- Are anxious

Transitions include, but are not limited to:

- Moving around the school

- Preparing for weekends and the start of holidays and beginning of term

- Moving from lesson to lesson

- Changing from structured to unstructured times

- Moving from break to lesson times

- Changes to staffing

- Special events (visitors, outings, celebrations etc)

Children told us

‘It’s better for me if teachers don’t ask me to answer questions when I haven’t put my hand up. If I get it wrong, I don’t like to try again in front of everyone’. Key stage 3 child

‘You can go to lunch club or use the computers if you don’t want to go outside, or you haven’t got any friends.’ Key stage 3 child

‘When we first joined, we had two weeks to get used to things and find our way round. There were no consequences for being late etc. We were all given a printed timetable. After that we knew where to go.’ Key stage 3 child

‘We move around and swap teachers for English and Maths to get ready for year 7.’ Key stage 2 child

‘We have tent in the classroom. You can go in there for time out. There are cushions in there.’ Key stage 1 child

Characteristics of good practice

- Schools get to know new children in advance through discussion with parents and previous settings the child may have attended

- For children transitioning in Early Years you can find some more information in our graduated response early years web page.

- Parents know what to expect and who to speak to if they have any questions.

- Children know what to expect and who to speak to if they have any questions.

- Induction days– more than just one day for those children who would benefit from additional support.

- 'Summer school’ for children transitioning from year 6 to year 7.

- Enhanced induction offers for some pupils this might include photos of school, photos of staff, communication passport, examples of a typical day, social stories, opportunities to take part in on-site activities e.g. workshops

- Preparation is made for those leaving school or education including enhanced offers for some children (see above).

- Safe space available within the classroom or an identified area of the school for time to re-regulate

- Visual timetables are used, events are removed or ticked off when finished. Timers

- Timers are used to show children how long they have to work for, and how long they have to finish.

- Opportunities for periods of respite using withdrawal to smaller groups. This may include self-directed / individual time-out.

- Plans are made for unstructured times: safe spaces are available; there are structured alternatives such as games club, use of library for vulnerable children.

- It is essential that school staff can support and understand the additional impact of:

- puberty

- birth of a sibling

- gender/ identity

- Change in parenting arrangements e.g., change in parent’s relationship status

- loss and bereavement

- accident or injury

- critical incident affecting school community

- School staff are familiar with relevant policies to support children

- Relationships Education Policy (Primary schools)

- Relationships & Sex Education Policy (Secondary schools)

See Surrey Healthy Schools: Taking a Surrey Healthy Schools approach.

- Theme 1: Whole School Approach towards the Promotion of Positive Health and Wellbeing

- Theme 5: Emotional wellbeing and mental health

Assessment planning, implementation and review

Expectation 1

A regular cycle of Assess, Plan, Do, Review is used to ensure that children are making progress.

Characteristics of good practice

- Child’s strengths and difficulties in learning and behaviour are observed and monitored in different settings and contexts for a short period of time to inform planning.

- Staff are aware of children’s starting points so that expected progress can be measured across each key stage.

- Assessment is used to inform planning and interventions.

- Consideration is given for individual child developmental trends. Case studies are used to demonstrate holistic progress.

Expectation 2

School staff ensure that formative assessment and feedback is a feature of lessons and evident in marking and assessment policy.

Characteristics of good practice

- A wide range of assessment strategies and tools are used to ensure a thorough understanding of learning.

- Children have regular opportunities to evaluate their own performance.

- Self-assessment is routinely used to set individual targets.

- The impact of interventions is critically evaluated. Alternative approaches are explored to establish whether they may result in better outcomes for the child.

- Recommendations for screening tools can be found in Surrey Inclusion and Additional Needs Schools Service Offer.

Expectation 3

School staff have the expertise required to manage reasonable examination arrangements (access arrangements) for tests and national tests and public examinations.

Characteristics of good practice

- Schools make adaptions to assessment arrangements as part of everyday practice. This is used to establish the leaners normal way of working.

- Please refer to the relevant exam board guidelines. Arrangements may include:

- rest breaks

- Use of a reader, scribe, or laptop

- Extra time

- Adapted resources are used in class and assessments.

Ordinarily Available Provision – Section B

This section is based on the four areas of need within the Code of Practice, it is a guide on how to support children in school.

The examples of provision, strategies, approaches, adjustments and specific interventions detailed in this section are not exhaustive, but a starting point for supporting children in school. The strategies and approaches detailed may not be suitable for all children and should be utilised where appropriate for the individual child.

The links provided are intended as a helpful tool for schools to use.

The examples given may not apply to just one area of need and should be implemented with flexibility based on the need of the child, the age and stage of the child, and the resources available to the school. Similarly, children’s needs do not always sit within one area and their individual situation may benefit from the strategies across more than one area. Where a child is accessing multiple strategies across the areas of need it is reasonable and appropriate for the school to start seeking further specialist input.

Please refer to the reasonable adjustment section for further guidance

Below we will outline the whole school approach, an example of a scenario for a child and then examples of provision and strategies that can be used in that scenario.

Communication and interaction

Whole school approach

- Whole school awareness and understanding of communication and interaction needs.

- Whole school audit of skills and training needs in relation to communication and interaction.

- Whole school CPD plan around communication and interaction.

- The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) can support schools to consider how inclusion is rooted in all school practices and help maximise the impact of new approaches.

What is happening for the child:

Difficulty saying what they want to say and being understood (descriptive language), which may include children with English as an additional language.

Example of provision and/or strategies, approaches, adjustments and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children

- Work with Parents to understand the techniques and strategies being used at home.

- Encourage Parents to become actively engaged with school life. Where English is an additional language, this could include sharing the language with the child’s class, providing key words and prompts.

- Check hearing has been tested

- Check understanding by asking questions/requesting feedback.

- Provide working area with minimal distractions where possible.

- Use the child’s name to gain and engage attention. Provide waiting time before engaging to ensure they have heard and have provided attention. Waiting time may vary depending on the child’s need.

- Use screening to identify how many information carrying words a child can manage and adjust language level accordingly when giving instructions.

- Dual coding and/or provide visuals to support with routines. Include – adaptions for notification if routines are to be changed?

- List of key words accessible per lesson on the whiteboard/presentation. This can be developed/adapted depending on age/need to list of key words accessible (in books or on laptops if being used) per topic that include definitions.

- Provide visual prompts to support language including key vocabulary, now and next, visual timetables, gesture, signing.

- Allow extra time to process what has been said. Time may vary depending on the child’s need and the task.

- Use standard instructions, and images that support understanding of concepts.

- Avoid use of sarcasm and idioms. Instead, explicitly teach about sarcasm and idioms where these occur in curriculum or are featured in a book/text.

- Communication cards, or universally understood signals to ask for help and indicate needs

Resources

Surrey Inclusion and Additional Needs Schools Service Offer

Specialist Teachers for Inclusive Practice (STIP) | Surrey Education Services

The Speech, Language and Communication Framework (SLCF) from the Communication Trust

Race equality and minority achievement (REMA)

Autism Outreach for Schools is commissioned by Surrey County Council and delivered by Freemantles School. The is to support mainstream schools to meet the needs of their autistic and neuro-diverse pupils or those undiagnosed but struggling in similar areas.

What is happening for the child

Difficulty understanding what is being said to them (receptive language)

Example of provision and/or strategies, approaches, adjustments and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children

- Working in partnership with Parents to identify strategies to support language development at home and school.

- Use gestures that reinforce positivity. Example – thumbs up, smile etc

- Allow time for the child to try and find the words they want to say. Time needed will vary depending on the child needs.

- Ensure there are opportunities for practising language. Example - circle time, small group work, when working with a partner.

- Encourage talking by commenting and giving choices rather than questioning.

- Try to avoid using idioms, “I’m all ears” or metaphors, like “Life is a journey”

- Provide an environment in which children can say when they don’t understand and can seek support to help them to work out which bits are difficult.

- Board games appropriate for the child e.g., Guess Who, Battleships can support with developing sentence structures, grammar, and vocabulary.

- Use of alternative methods of communication. Example - simple signing techniques, picture exchanges etc.

- Where difficulty is with speech and/or fluency. Have key words with supporting images visible in all classrooms.

- Be honest and don’t pretend to understand. Offer reassurance that you want to understand and that together you will both find a way to work it out.

- Use assistive technology where appropriate

Resources, advice and support available

Specialist Teachers for Inclusive Practice (STIP) | Surrey Education Services

The Speech, Language and Communication Framework (SLCF) from the Communication Trust

Surrey County Council Literacy for All programme: Surrey Education Services Hub

What is happening for the child

- Child is confused and may be frustrated by social rules of communication.

- Child is not able to take turns, share, exchange greetings, take part in active listening,

- Child is confused by the feelings of others, and the demands of others to show respect or resolve conflict.

- Child may be finding it hard to make and maintain friendships.

Example of provision and/or strategies, approaches, adjustments and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children

- Ensure you are following all the advice for difficulties with receptive or expressive communication. Allow additional time for processing of information, especially verbal information.

- Simplify language as necessary; speak slowly, give instructions in order, use gestures and visual aids to support understanding. Don't assume understanding.

- Use of visual prompts and reminders for the social expectations

- Where rules are essential for safety and well-being, use a variety of scenarios to demonstrate where or when the rule applies.

- Provide opportunities to practice throughout the school day and week. This may be through a combination of formal teaching or social interactions.

- Praise all communication attempts.

- Have clear expectations and use consistent language to talk about the expectations.

- Consider the use of a ‘whoops card’ to support children when things go wrong, and/or plans are unexpectedly changed.

- Incorporate time for special interests each day/week.

- Be aware that children’s ability to process language may be reduced when they are angry or upset.

- Be aware that Adults become dysregulated too and are less likely to respond to the child’s needs appropriately when they are angry or upset. Seek support of colleagues who can step in If needed.

- Adults recognise and respond appropriately to emotional dysregulation by modelling emotional regulation strategies when they make a mistake. Consider, tone of voice, body language etc

Resources, advice and support available

Specialist Teachers for Inclusive Practice (STIP) | Surrey Education Services

What is happening for the child

Child is overwhelmed and unable to speak due to the anxiety they are experiencing

Example of provision and/or strategies, approaches, adjustments and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children

- Work with Parents and Carers to understand what is happening at home and to understand the strategies used at home to support and reassure the child.

- Concentrate on developing meaningful relationships, building and developing trust. Children should have access to a consistent key worker. Where possible 1:1 sessions of 20 minutes three times a week, can help with building a verbal relationship with someone in school.

- Acknowledge other strengths and use these to build self-esteem.

- Avoid ‘cold calling’ on individuals to answer questions in front of the whole class.

- Provide opportunities for children to talk when they are ready, or to communicate in a way that is more comfortable for them. Example: ‘show me’.

- Avoid causing embarrassment. Where this happens apologise and work with the child to develop strategies that will prevent this happening again

- Avoid rewards and sanctions, instead focus on collaborative problem solving around areas of difficulty. Consider this within school behaviour policies.

- Where practicable establish common practise throughout the school for teaching staff not to call on individual children to answer questions in front of the whole class.

- Reduce the number of questions you ask, as this puts pressure on the child to talk. Example: instead of saying ‘what’s that?’ say ‘look, a tree’. Where there is a need this provides a language model without putting pressure on them to speak.

- Where a language model is not required, reword questions into rhetorical comments that provide opportunities to speak, without pressure. Examples: ‘I wonder what would happen if we did it like this…’

- Provide clear structure. Where helpful, include time frames for tasks. Example: using a timer.

- Encourage participation in games that do not require talking. Let children know that they don’t have to talk to join in with the game.

- Encourage non-verbal communication where this is preferred, whilst developing confidence with speech. Example: eye contact, gesture, drawings, and writing.

- Where the child finds non-verbal communication anxiety provoking, through your relationship with the child develop an understanding of how they would like to communicate non-verbally whilst developing their confidence to speak.

- Where possible give autonomy over how a learning objective can be achieved based on the child’s skills and preferences. Example: option to produce a PowerPoint instead of writing an essay. Be clear that there is no requirement to ‘present’.

- Consider using choice boards alongside of visual timetables. Older children may prefer a printed copy of their timetable that can be laminated.

- Allow access to regulating activities throughout the day.

Resources, advice and support available

How to Help a Child With Selective Mutism in the Classroom (Selective Mutism Association)

Information for Professionals (Selective Mutism Information and Research Association)

Example - Selective Mutism

It is not a choice, but I may find it hard to speak at all and I might:

- Speak only in certain environments, e.g., at home. Only speak to peers but not adults.

- Only speak to my key adult.

- Find it difficult to speak to you when anxious.

- Not smile or look blankly.

- Appear awkward/uncomfortable around others.

- Find it difficult to have simple interactions such as saying hello.

- Worry more than others.

- Have good concentration skills.

- Be sensitive to noise and other environmental stimuli.

- Be very sensitive to the feelings of others.

How to respond:

- Increase your understanding of selective mutism through national support and research.

- Acknowledge the fear of speaking, with the child, but do not ask why a learner can’t speak.

- Demonstrate patience and understanding.

- Remove speaking pressure and don’t plan activities that cause anxious responses.

- Do not reward and openly praise when a learner attempts to speak.

- Avoid asking individuals to read aloud or answering questions in front of a group.

- Offer opportunities to contribute to fully include the learner

Social and emotional mental health

Whole school approach

- Partnership working with the child and their family that allow regular opportunities to reflect on and plan for child’s wellbeing and behaviour.

- A Mental Health Policy underpinned by an inclusive ethos and values with clearly communicated expectations around behaviour and engagement.

- Use of whole school approaches to promote wellbeing and resilience.

- Training on building and maintaining relational approaches in schools.

- Training on Adverse childhood Experiences (ACEs), and attachment.

- Imbed restorative approaches to build, maintain and repair relationships.

- Anti-bullying work, Keeping children safe in education - UK Government website

- Curriculum design, PSHE, and circle time provide explicit opportunities to discuss and negotiate rules and routines, that keep us safe, build self-esteem, and develop social and emotional skills for all children.

- Develop attachment aware strategies (training available from the Virtual School and Educational Psychology Service ).

- Small team of key adults identified and available for children who need them.

- Reasonable adjustments for SEMH – refer the reasonable adjustments section

What is happening for the child

Difficulties participating and presenting as withdrawn or isolated, significantly unhappy or stressed

Example of provision and/or strategies, approaches, adjustments and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children

- Work with Parents to understand what is happening at home.

- Partnership working with Parents to support children who mask their difficulties in school.

- Understand that school intervention can support wellbeing at home and vis versa.

- Take time to find out about the child’s interests, strengths, things that are important to them outside of school.

- Allocate a key person/peer/adult/teacher to that child.

- Provide regular check-in and/or reassurance opportunities. This may be a time the child can come to you, or a time when you go to find them.

- Use teaching assessments to identify areas of strength or particular interest within the curriculum. Use these to develop and build confidence.

- Complete a simple language screen to rule out any difficulties with communication that the child may be masking.

- Use ‘emotion coaching’ strategies to guide and support children to understanding their responses to tricky situations.

- Small group work opportunities with friends or social skills, nurture groups.Buddying and peer mentoring.

- Give responsibility for looking after someone else, where appropriate.

- Facilitate the development of friendships through clubs

Resources, advice and support available

Emotion Coaching Resources for Professionals

Surrey Inclusion and Additional Needs Schools Service Offer

Compassionate schools’ community of practice

Surrey Child and Family Health

Promoting and supporting mental health and wellbeing in schools and colleges - UK Government website

Toolkit for schools: communicating with families to support attendance - UK Government website

What is bullying? (Anti Bullying Alliance)

What is happening for the child

Child is seeking connection by exhibiting behaviours that staff may find difficult to manage, e.g refusal to follow instructions, aggression, damage to property

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Work in partnership with parents to understand what is going on for the child and together, identify ways to best manage this at school and home.

- A consistent message with a flexible approach. Example – ‘I want you in class so that you are learning…’, is the consistent message, the approach to support this happening may vary depending on individual needs.

- Draw up a risk assessment.

- Seek support from other professionals where necessary.

- Have clear boundaries and expectations of all children. Where possible, provide opportunities for all children to be involved in the process of setting these.

- Support the child to understand that anger is a normal emotion like any other and provide strategies to help manage it. Example – daily exercise, walking away from a situation, taking a walk to calm down, spend time in the sensory room, provide a space to vent frustrations, someone to talk to.

- Use of choices to give the child some control. Example - would you like to talk to me now or later?

- Use of distraction techniques, provide opportunities for responsibility where appropriate.

- Where sanctions are imposed, ensure there is time for everyone involved to reconnect afterwards.

Resources, advice and support available

My Safety Plan (Mindworks Surrey)

Specialist Teachers for Inclusive Practice (STIP) | Surrey Education Services - Positive Touch Training

Support Planning - Challenging Behaviour Foundation

'Understanding links between communication and behaviour' factsheet from Speech and language therapy factsheets | Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists

What is happening for the child

Behaviours that may reflect mental health concerns (anxiety, depression, self-harming, substance misuse, eating disorders)

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Speak with the child to understand what the problem is.

- Collaboration with parents/carers is essential to understand what is happening for the child.

- Has the behaviour changed and if so, when – is there an opportunity to revisit and restore?

- Take a relational approach and seek to understand the behaviour. Consider both positive and negative behaviour. Is there a pattern when the behaviour happens? Keep a log.

- Safeguarding/ risk assessment.

- Multi-professional approach – can also include internal school colleagues. Example - school’s mental health lead, and/or key adults who have a good relationship with the child.

Resources, advice and support available

Emotion Coaching Resources for Professionals

Compassionate schools’ community of practice

Surrey Child and Family Health

Promoting and supporting mental health and wellbeing in schools and colleges - UK Government website

What is bullying? (Anti Bullying Alliance)

What is happening for the child

Physical symptoms that are medically unexplained. This may include but is not limited to; soiling, stomach pains, headaches etc

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Use the Parents knowledge of their child’s situation and replicate the strategies in place at home in school, where possible.

- Work with Parents to develop a (short/mid/long-term) plan.

- Provide access to activities that reduce stress. Examples include games, dance, colouring, crafts, gardening, animal care time outdoors, Lego play.

- Keep a log and analyse pattern or trends to identify triggers.

- Seek support from the school nursing team.

Resources, advice and support available

Surrey School Nursing Support for Schools | Surrey Education Services

What is bullying? (Anti Bullying Alliance)

Surrey Child and Family Health

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) Society

What is happening for the child

Attachment difficulties, including Attachment Disorder

N.B. provision or support should be provided in line with the needs of the child and not dependant on a formal diagnosis

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Nurturing approaches and ethos/ nurture groups.

- Work to establish a trusting relationship with parents and carers that will improve understanding of family context.

- Staff training to develop an understanding of the wide range of children that may have attachment difficulties, e.g. adopted children, forces children, previously CIN, Looked After Child (LAC), other vulnerable children.

- A fully planned for transition when the child joins the school that allows for an understanding of the child’s life story and experiences so far.

- Supportive, structured school curriculum.

- Staff to all be trained and aware of any child with attachment difficulties and how to respond to them.

Resources, advice and support available

Surrey Virtual School (SVS) - Surrey County Council

Specialist Teachers for Inclusive Practice (STIP) | Surrey Education Services - Positive Touch Training

Attachment and child development

What is happening to the child

Low level disruption e.g., talking out of turn, frequent interruptions to learning, fiddling with objects

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Explicit teaching and revisiting of school’s behaviour policy. Please note, behaviour policy should reflect an inclusive ethos.

- Consider a language screen e.g. ‘Language for behaviour and emotions’ to confirm that the child understands the language of expectations linked to behaviour. Explicitly teach the expectations linked to behaviour.

- Differentiated use of voice, gesture, and body language.

- Focus on reducing anxiety by providing a safe and calming environment.

- Flexible and creative use of rewards and consequences

- Positive reinforcement of expectations through verbal scripts & visual prompts.

- Offer a ‘safe space’ for self-regulation, where possible.

- Staff training in de-scalation approached to reduce anxious behaviours. Example the adult using concise and clear instructions, delivered in a calm and assertive vocal tone.

- Provide opportunities for movement breaks

Resources, advice and support available

'Understanding links between communication and behaviour' factsheet from Speech and language therapy factsheets | Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists

What is happening for the child

Difficulty in making and maintaining healthy relationships

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Small group/nurture group activities to support personal, social, and emotional development.

- A range of differentiated opportunities for social and emotional development e.g., buddy systems, friendship strategies, circle time.

- Use restorative approaches

Resources, advice and support available

Promoting healthy relationships in schools

Understanding Masking | Kids Charity

Autistic Masking Symptoms - Signs, Traits, Effects

What is happening for the child

Difficulties following and accepting adult direction

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Avoid power struggles and/or becoming dysregulated yourself

- Look for patterns and triggers to identify what may be causing stress and anxiety.

- Positive scripts - Positive language to re-direct, reinforce expectations e.g., use of others as role models.

- Calming scripts to deescalate, including for example, use of sand timers for ‘thinking time’

- Limited choices to engage and motivate.

- Flexible and creative use of rewards and consequences

- Visual timetable and use of visual cues i.e., sand timers to support sharing, or ending a task

Resources, advice and support available

'What helps?' guides - PDA Society

Teacher's guide to understanding PDA from SEND Supported resources library

What is happening for the child

Presenting as significantly unhappy or stressed

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Feedback is used to collaborate and plan with parent or carer, to ensure consistency between the home and setting.

- Identify and build on preferred learning styles.

- Identify a safe place/quiet area in the setting, where possible.

- Talking Mats and Comic Strip Conversations may help to identify triggers. Social Scripts and Social Stories can help support children to develop self-help strategies.

Resources, advice and support available

Social stories and comic strip conversations

What is happening for the child

Patterns of non-attendance or emotionally based nonattendance

Example of provision and/or strategies, approaches, adjustments and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children

- Home-school meetings to develop a shared understanding of the factors contributing to the non-attendance (i.e., the function of the non-attendance), drawing upon best practice guidance e.g., West Sussex guidance on Emotionally Based School Non-Attendance (EBSNA) toolkit.

- Meeting with child to understand their perspective around non-attendance, using resources on the EBSNA Padlet (see link above).

- Named key adult maintaining daily communication, to include wellbeing checks and ensuring provision of work if not in class/not attending school.

- Support plan in place, developed with the child, school and parents/carers.

Resources, advice and support available

Educational Psychology Service | Surrey Education Services

School Anxiety and Refusal | Parent Guide to Support | YoungMinds

Tips for supporting children who are experiencing school non-attendance - Psychology Associates

Cognition and Learning

Whole school approach

- Whole school staff awareness of the principles of assessment through teaching and evidence-based approaches to intervention

- Review of Behaviour Policies (including rewards and sanctions)

- Assessment for Learning formative assessment

What is happening for the child

Child finds it hard to concentrate and listen in the learning environment

Examples of provision and/or strategies: approaches, adjustment and specific interventions that school settings can apply and adjust according to the individual needs, age and stage of the children.

- Talk with the child about strategies that may help them to organise themselves, ensuring they have the equipment they need, and help them to practise using these.

- Engage with Parents/carer to understand strategies in place at home.

- Be aware of times of the lessons/time of day that may be more difficult.

- Promote and encourage an uncluttered learning space.

- Consider seating position that will encourage optimum engagement.

- Reduce background noise. Example - keep classroom door closed to reduce competing noises.

- Identify the best way to obtain the child’s focus. Example – by saying their name, using a rain maker, using visual clues

- Be an engaging speaker. Example - show enthusiasm, use body language to emphasise points, vary pitch, volume, and intonation. Vary the teaching methods. Example - such as sound clips, videos, rhymes.

- Movement breaks may be helpful. Establish clear boundaries and mutually agree the how and when these can be used. It may help to have a place for children to go if they need a movement break i.e. student reception, where there is always an adult who can check-in with them. It may also be helpful to log the times that the child is using movement breaks to help identify patterns or triggers.

- Give information in short chunks, repeat, and give time for processing. Amount of time may vary depending on the child’s need and the task.