The world of William More

One morning, on 25 January 1677, Sir William More rode out from his Loseley estate near Guildford, perhaps clad in his new leather 'spatterdashes' (6s) against the season's mud and arrayed in his fine new sword (£2 3s 6d), and headed for his manor of Haslemere. Visiting Mr Wall's en route, he paid 2s, probably tipping servants for 'horsewarming' and otherwise tending his mount. At Haslemere he spent 2s 7d on refreshments, £1 5s on business, and visited his Uncle James (4s 6d in tips); by the time he reached Mr Elliott's (Busbridge), his travel-worn clothes needed sprucing (4s 6d). The return to Guildford called for the barber (2s 6d) and further imbibing at one of his regular establishments, Mrs Robinson's (3s 2d).

One morning, on 25 January 1677, Sir William More rode out from his Loseley estate near Guildford, perhaps clad in his new leather 'spatterdashes' (6s) against the season's mud and arrayed in his fine new sword (£2 3s 6d), and headed for his manor of Haslemere. Visiting Mr Wall's en route, he paid 2s, probably tipping servants for 'horsewarming' and otherwise tending his mount. At Haslemere he spent 2s 7d on refreshments, £1 5s on business, and visited his Uncle James (4s 6d in tips); by the time he reached Mr Elliott's (Busbridge), his travel-worn clothes needed sprucing (4s 6d). The return to Guildford called for the barber (2s 6d) and further imbibing at one of his regular establishments, Mrs Robinson's (3s 2d).

He might little have guessed how fascinating his daily doings would be to us, some 300+ years later. William's memoranda and ephemera survived among his family archive, usually known as the 'Loseley Manuscripts', deposited with us in 1950. Catalogued until recently as a 'volume of accounts', the fragile pages were in fact loose, only bound together by a lacework of mould, with areas of text fused apparently irremediably. Restoring the 17th century world here recorded needs very many exacting hours of conservation work, and some detective work too.

He might little have guessed how fascinating his daily doings would be to us, some 300+ years later. William's memoranda and ephemera survived among his family archive, usually known as the 'Loseley Manuscripts', deposited with us in 1950. Catalogued until recently as a 'volume of accounts', the fragile pages were in fact loose, only bound together by a lacework of mould, with areas of text fused apparently irremediably. Restoring the 17th century world here recorded needs very many exacting hours of conservation work, and some detective work too.

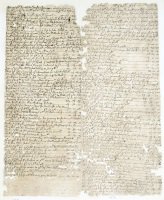

William used the pages as a journal of all kinds of receipts and expenses as they occurred, and probably as an aide-memoire to any other business as he recalled it (he did write up rationalised accounts, but these have not survived). The jumble, covering 1672 to 1683, includes payments of tax for his 37 chimneys (£3 14s), expenses of brick-making for his estate, generous quantities of claret and port, a beagle called Dash and a cross bow (£2 3s), 1s to Eagles and his company of fiddlers (at Loseley till 2am), a taste for violet syrup (2s), a game of bowls at Hascombe (3s) and a charge to his mother-in-law for her board. We think he may have kept the pages with him, as a heavy horizontal fold down their middle suggests that they may have been folded for convenient carrying - perhaps in a saddle bag while out and about. (On longer trips he might keep track of his cash: '£1 6s 4d in my pocket'.) The long narrow pages are a common format for an account book, so William may have intended the folded sheets to be stitched into a volume once enough were completed; the accounts cover the last years of his life, 1672 to 1683, until around six months before his death, aged 41.

The restoration

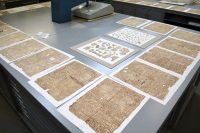

The first stage of the restoration is the removal of loose dirt and mould and the separation and stabilisation of the highly delicate sheets. A full 60 hours of work later, the pages are ready, arranged in the order in which they were found: we can now attempt to check, and if necessary reconstruct, their chronological sequence.

The first stage of the restoration is the removal of loose dirt and mould and the separation and stabilisation of the highly delicate sheets. A full 60 hours of work later, the pages are ready, arranged in the order in which they were found: we can now attempt to check, and if necessary reconstruct, their chronological sequence.

Each folded sheet has two possible configurations of its four sides of text. The 'V' may read in the order A B C D opened one way, or C D A B opened the other. We must read the evidence carefully. William, like most Englishmen of his day, counted 25 March as the start of his year, so we must recognise that his January 1676 occurs after his December 1676 (and is our 'New Style' January 1677). William gives sparse clues as to year date (after all, at the time, he knew it). Other dates are lost where the paper has disintegrated. The majority of payments are confusingly in arrears. We must interpret what we can.

At the end of this stage, the sheets have been sequenced. Smaller fragments are examined: Norwegian coastlines of soft, aged paper, can sometimes be coaxed to match, first by eye, then with tweezers, then by sense, as both sides of text are critically compared.

At the end of this stage, the sheets have been sequenced. Smaller fragments are examined: Norwegian coastlines of soft, aged paper, can sometimes be coaxed to match, first by eye, then with tweezers, then by sense, as both sides of text are critically compared.

Now each sheet is being repaired and will finally be bound into a whole. We can become familiar with William and the progress of his busy days, the company he kept – servants, family, gentry, professional men and tradespeople - his business affairs, his likes and pastimes.

William's journal is neither comprehensive nor systematic, but, brought back from ruin, is truly rewarding. From this decayed filigree of ink we can again read the vivid tangle of tiny threads which wove the life experience of the man.

See also

Images

Select image to view a larger version.

- Extract from accounts journal of Sir William More, 1672 to 1683, reference LM/1087/1/12

- Full page from accounts journal of Sir William More, reference LM/1087/1/12:

- Journal before restoration

- Damaged pages

- Pages laid out in conservation studio